When I was a kid living the middle of nowhere we got four TV channels (five if it was cloudy and the rabbit ears were twisted just right). In the heady days before the FCC allowed local station roll-ups, this meant I was served a steady diet of weird B-movies and syndicated re-runs. And as someone who watched a lot of TV it meant my cultural references were and remain slightly skewed and a little anachronistic.1 Which is all to say: this is how I came to write a post using a catchphrase from a show that ended seven years before I was born as the organizing metaphor.

Gomer Pyle, USMC was a spin off The Andy Griffth Show. Gomer, our protagonist, was the local mechanic of Mayberry, North Carolina, the fictional town where Andy was the goodhearted sheriff. When that show ended in 1968 (thanks, Wikipedia), Gomer enlisted in the Marine Corp and further hilarity ensued. The premise of the show was classic fish out of water. The good-natured Gomer confronting the stifling rigidity of the American military. Week in and week out, Gomer’s humanity won out over the dehumanising inflexibility of the total institution and many nefarious characters within and outside it. And when his simple everyman wisdom shone through the malfeasance or indifference of that week’s 30-minute challenge he’d always smile broadly and declare, “Surprise, Surprise, Surprise” in his exaggerated southern drawl.

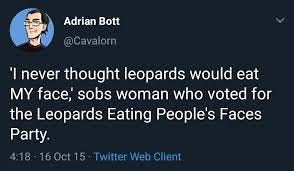

As someone who makes a living as a management consultant, I think of Gomer’s proclamation almost daily.2 Much like voting for the leopard’s eating people’s faces party, management consultants work with clients to undermine their own position, only to loudly proclaim dismay when it happens. Surprise, Surprise, Surprise!

What I’ll call the “co-created screwing process” emerges from a tension central to management consulting. The profession exists, at a surface level at least, to help companies build market power.3 By helping companies to define and excute strategies, improve operational performance, enter new segements, launch new products, buy other companies, etc. consultants support firms to become more powerful versions of themselves, better able to shape their wider environment. What consultants tend to miss is that they’re also part of that environment and will eventually come to be on the receiving end of this enhanced power. It’s a funny state of affairs.4 A profession (of sorts) that prides itself on working with - it’s a partnership! - clients to co-create their preferable futures all while sowing the seeds of their own eventual screwing!

The process takes shape in three overlapping parts.

Part 1: consultancy growth

Consultancy works like a classic Abbotian profession.5 It is arrayed by status according to client served (both across industry and within organizations, think C-suite vs. Head of; Strategy vs. HR). When you’re a single shingle, you have the freedom to roam a bit more freely in search of work and status fulfilment. But once a consulting firm breaks five-ish people suddenly there are overheads and internal management requirements. Feeding that beast means specialization to garner higher fees which only the largest firms will pay.

Here’s the rub. Consultancy firm growth, to a point that is very hard to break, is pinned to increasing specialization and fee justification. Whatever the firm’s fee structure - time and materials, value-based, or contingency - it’s status (of buyer and seller) that justifies the fee. And that status is at least partially fed by access to cultivated and managed professional knowledge that is controlled by the profession (through whatever means: accreditation, regulatory barriers, tools, time required to learn, etc.). This first phase creates the double-bind. The need for greater cashflow forces a search for fee improving capabilities forcing greater specialisation in turn narrowing the field of potential buyers.

Part 2: client growth

Scratch the surface of any consultant and they’ll tell you how they’re ultimately helping clients perform better. It’s all about growth - however measured - and they’re offer is driving it directly or indirectly. Setting aside for a moment the individual strength of those claims, we can safely assume that consulting as profession contributes, in some way, to driving firm growth, furthering the development of market power. For the purposes of this discussion I’m principally interested in two growth drivers.

Activities specifically geared towards growing market power. This includes consulting focused on strategy, M&A, marketing, regulatory chicanery, etc.

Consultants as vector. A big reason firms hire consultants is to gain insights into what other firms are doing. Consultants become carriers of ideas - generated internally or with clients - across firms.

This market and business shaping advice reinforces and expands firm and industry level market power. The drivers in pot 1 explicitly support firms to gain power at the expense of other firms, narrowing the number of potential buyers. The drivers in pot 2 are isomorphic, making everyone look more like everyone else. This in turns limits the opportunities for consultancy firms to present unique pricing to different clients because clients have been designed, trained, or taught - by consultants - to manage consulting projects and fees in more uniform ways. Together the approaches, frameworks, tools, strategies, whatever shared to support client businesses to look and behave like everyone else, end up reducing the total buyer set, and granting that reduced market the tools to continue screwing other market actors, including consultants.

Part 3: market consolidation

The last part of the co-creation screwing process is market consolidation. Like shingles on a roof, the needs of consulting organizations to sell more expensive work to survive overlaps with those very same projects reinforcing firm or market-level power to further narrow the available market for services. Co-created efforts to expand / consolidate market power on behalf of clients create the conditions for screwing over the very consultants that so proudly helped their clients achieve these lofty goals.

Fewer, more powerful firms create a monopsonistic market where a small number of powerful buyers get to call the shots for buying, pricing, and even directing the development of labor. Consulting firms have actively worked with clients to co-create the circumstances of their own screwing.

Don’t hate the player…

My objective here wasn’t to make management consultants objects of sympathy. (Honestly not sure under what circumstances that’d be possible.) But rather to explore the dynamics shaping the profession’s current doldrums.

Without doubt billions have been spent on fruitless projects, innumerable clients simply don’t “implement well”, and more than a little snake oil has been peddled as cure all. But the role of the profession in creating the circumstances of its own screwing is all too often overlooked. By simply doing what they proclaim to help businesses to do they have co-created the circumstances of their own relentless shafting. By supporting the development, expansion, and reinforcement of market power the profession has directly contributed to their current predicament by shrinking the number of buyers, reinforcing this cadre’s bargaining positions, and training them how to win at increasingly uniform competitive games.

It doesn’t take the genius of Gomer Pyle to see that the industry has directly contributed to own screwing. Surprise, surprise, surprise!

The B-movies on Channel 40 (UHF!) were always sponsored by some local building contractor. They sat in deck chairs on a set designed building site saying things like “Fatty, Fatty 2x4 can’t get through the kitchen door? Well, call us to widen it.”

I still hold on to a self-soothing internal narrative that I’m just a sociologist working in an applied setting. Maybe I inhabit an interstitial space; maybe I’m lying to myself?

Like any “thing” we do lots of different activities simultaneously: mechanism to prove companies are doing something; proxy for internecine warfare between internal teams who can’t directly engage; consumer of end of year budgets to ensure next year’s allocation, etc., etc.

One I’ll admit I would find less financially threatening if I were outside of it.

Am I ok to refer to Andrew Abbott this way? I mean, he looms large in my worldview so I’m going to take it. Check out his The System of Professions for more on this professional hierarchy by client type and status.