To my mind every week is a bad week for behavioral science, but this last week has been a doozy. In less than seven days, one of the field’s superstars, Francesca Gino, has been accused of committing fraud in at least four published papers and has been placed on administrative leave by Harvard Business School where she teaches. In the same week, the Federal Trade Commission has filed a “heavily redacted complaint” against Amazon for their use of “dark patterns”: deceptive design models used to trick (or perhaps just grind down) users into transactions they do not intend to make. It’s not exactly been a banner week for the nudge community.

Let me start with a brief background before I move to the airing on grievances.

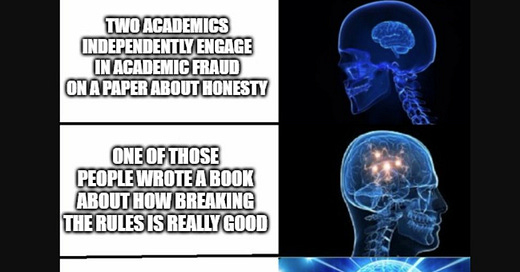

Scandals all the way down

Beginning on June 17th, the team at Data Colada, an academic blog published by three respected behavioral scientists, published a four-part series detailing evidence of fraud across a set of papers co-authored by Francesca Gino. You can find them here: part 1, 2, 3, 4 (forthcoming). Subsequently, the reports of (alleged) fraud were picked up by the Chronicle of Higher Education on June 22nd and has since been profiled in the New York Times, the Financial Times, and Science, among others.

That seems like a lot for an academic dispute, I hear you say. But this is no ordinary academic dispute. Behavioral science is one of those rare academic breakouts with so-called “real-world application”. From airport book best sellers to ppt slides on change management, behavioral science is all over the place outside the hallowed halls of higher education. Mixing, as it does, lay peoples’ awe of (seldom understood) mathematical formalism and the pervasive belief that most things can be explained via mental events, it combines two of the non-academic world’s favorite go-to academic subjects economics and psychology.1

And real world application doesn’t get more real than Amazon’s use of dark patterns. A core principle behavioral science as practiced is a pervasive sense of design determinism. The idea that interactions may be structured into quasi-experiments where design elements shape behavior in desired ways is how we got dark patterns. A process so complicated and cumbersome, their internal team called it the “Iliad Flow”. But unlike the studies (many of which have either not replicated, shown to be based on falsified data, or simply products of good old fashioned p-hacking) that claim that small design changes can yield big shifts towards desired outcomes, the reality in practice is that it’s just lots of just active deception parading under the banner of “science”.2

Together these two recent scandals highlight that poverty of theory underpinning this field.3 But the real crimes are in the application. I fled academia almost two decades ago but every day is yet another encounter with bastardized versions of these frankly terrible ideas. If I thought conclusions drawn from samples of undergrads taking an intro to psych course and published as universal laws were bad, I simply was not ready for the horrors of lay applications. From nudge units to wheels (it’s always wheels!) categorizing thought patterns, user types, and need states, the belief that we can drive big changes with small shifts and reduce the complexity of social life to consistent, universally applicable rules deserves its own courts at the Hague. In preparation for that inevitable, beautiful day of reckoning, I set out my three primary beefs with behavioral science. Consider this the outline of my eventual amicus curiae.

Three beefs

I have three primary beefs with behavioral science. I was going to try and tease out my issues with the field as academic practice and as bastardized in “real world” settings but then I realized that venn diagram is a circle.

1. The world isn’t an experiment

The means by which reality is interrogated to produce an explanation is garbage and doesn’t fit the subsequent contexts of applications.

One of behavioral science’s biggest claims to authority rests on its use of experimental methods. Modelling themselves on natural scientists, the assumption is that by using the controlled conditions of an experimental context, they are able to tease out the mechanism of change.4 These experiments are more often than not run on convenience samples of undergraduate students with the assumption being that people are people are people. The issue under study is generally individual-level cognition which, in this approach, is assumed to be universally consistent. That is, it doesn’t matter who the subjects are, the mental processes under evaluation are (nearly) universally consistent and applicable across contexts.

The problem is the world doesn’t operate like an experiment. This wouldn’t necessarily be an issue if the process at play here were one of mechanism identification to explain a larger events or class of events but behavioral science as practiced generally presents itself as identifying universal laws or mechanisms of explanation. The insights drawn from the experimental context is presented and interpreted by lay-users in particular as laws ready for universal application. They are then used like a recipe. And as they align with popular belief about how the world works, the failure of the recipe to produce the desired outcome generally goes unquestioned. All that matters is that the ritual is followed.

2. Mental events aren’t responsible for social life

There is no clear mechanism or mechanisms that get us from things happening in people’s heads to life outside of it.

The “behavior” part of behavioral science is a bit of a misnomer. The primary object of study is mental events. The logic flows something like this: we can run experiments to induce behavioral outcomes that provide insight into what’s happening in people’s heads. And from these, we can discern the rules of social life and explain how higher order events manifest. There are three problems with this perspective.

There is no clear link between mental events and what people actually do. Most explanations are retrospective. And humans are terrible narrators of their existence.

There is no clear mechanism for getting from mental events to larger patterns (anything beyond very small group encounters). Despite what opinion polls claim to show us, we can’t simply aggregate our way from stuff people tell us (or undergrads show us in “lab” settings) to the patterns that shape our lives.

The flow is all wrong. As Erving Goffman wrote in 1967, it’s not “men and their moments. But moments and their men." [sic].5 Think about it, we’re different people at home vs. work vs. school vs. church vs. war. We don’t carry all those logics with us, the context induces it. Trying to explain behavior, change, and wider existence via recourse to mental events requires leaps of faith more suited to a tent revival than a boardroom.

3. Where’s emergence and change?

We can’t explain things by simply adding together supposed mental events. More is different.

Behavioral science loves to evaluate small groups and then aggregate or extrapolate the findings to wider contexts. But as (nobel laureate, see, I’m not above my own status grabs) PW Anderson wrote in 1970, more is different.6 Reductionist paradigms can’t explain emergent phenomena. We can’t distill the rich complexity of a business organization or even a status update meeting via an aggregation of mental models held by the participants. They are emergent. They draw on but are greater than the their parts.

And what of change? If we allow that mental models are responsible for social life, then how do they change? The thing about laws is that they’re only laws when they’re immutable. But we know that cognitive approaches themselves change over time and by context. Behavioral science (particularly as practiced in the corporate world) is a deadend. It offers no explanatory means by which new things develop, embed, and change over time and across places.

We deserve better

My Seinfeldian airing of grievances will do little to shift the true believers. Planck’s Principle reminds us that theories don’t die, their adherents do.

But given the time, efforts, money, and attention devoted to the expansion and application of behavioral science, recent scandals should do more than offer pause for reflection. We deserve better than comforting nonsense.

It’s not a pure mix. Lots of social psych and org psych in this devil’s mix too (don’t get me started on this contradiction in terms. How can an inherently collective, emergent phenomenon like organization be explained in terms of psychology?!)

Maybe that’s too harsh. I’m sure we could create experimental conditions that definitively show that ambiguity of a process yields bad “player” outcomes. I mean, there are a lot of journals out there and some where’s bound to publish it.

Shout out to my EP Thompson stans.

I almost wrote causation but I don’t need that fight today.

Only citation, promise. Goffman, Erving, 1922-1982. 1982. Interaction Ritual: Essays On Face-to-face Behavior. New York, Pantheon Books.

I plugged this post on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/geraldlombardi/recent-activity/all/

That platform is so overfilled with praise for the business-idea-of-the-month, I figured it would be a good antidote.

Would love to hear some juicy stories about disastrous applications of behavioral science principles. Did they precipitate the Bud Lite debacle?

Imagined Dialog: "Okay, we'll take the most countryfied, manliest beer in America, and we will capture attention and stimulate mental events by parading around a she-male. And the burst of psychic energy will vastly boost sales especially if she's wearing yellow."